J.C. Leyendecker: Norman Rockwell, but First and Make It Gay

Chances are you've heard the name Norman Rockwell, famed painter of idyllic Americana scenes that graced the covers of hundreds of editions of The Saturday Evening Post during the 1900s, but just as likely you haven't heard of his predecessor: One Joseph Christian (J.C.) Leyendecker.

Portraits of Artists from Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (public domain, photographer unknown)

Rockwell saw Leyendecker as one of his main inspirations, and he is regularly called Rockwell's "mentor." He too created hundreds of covers for The Saturday Evening Post, and created advertorial illustrations, most notably the famous "Arrow Collar Man," and the "Chesterfield Man," both of which were seen as the ultimate male sex symbol in their day, especially the former, who was delivered with a mix of ruggedness and refinement that helped define the era.

In fact, it's believed the Arrow Collar Man is who is being referenced by Daisy in The Great Gatsby when she tells the novel's namesake that he looks "so cool," resembling "the advertisement of the man."

Chase, Arrow Collar, 1923

Rockwell was so taken by Leyendecker and his work that he did everything he could to absorb the man's artistic style, and even his very essence.

As he wrote in his autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator, where he said he, as American Illustrators Gallery summarized, "followed Leyendecker around New Rochelle, New York, emulating Leyendecker’s swagger, or limp as it were, and 'attitude.'"

Record Time, Cool Summer Comfort—House of Kuppenheimer Advertisement, 1920

While Rockwell was transparent about his influence, and while Leyendecker was well known in his day, his name has been largely forgotten, with Rockwell's work replacing his in the collective American consciousness as the quintessential 20th century American illustrator.

Part of this newfound interest in the man and his work has led to a deeper discussion of his personal life, including the fact that he was gay.

Arrow Collars Advertisement

Leyendecker, who emigrated to the United States from Germany with his family, which included his brother, Frank Xavier (F.X.) Leyendecker—a talented illustrator in his own right, who is also believed to have been gay—met 17-year-old model Charles Beach when he was 29. He was taken by the young man's good looks and began using him in his work.

He would become the prototype for the Arrow Collar Man, and also be used as a reference model for a number of his other projects. The two would go on to live together for the majority of their adult lives, presumed to be partners. Beach would also serve as Leyendecker's business manager.

While Leyendecker's illustrations might seem tame by today's standards, his love for the male form and masculinity generally is evident. He was fond of depicting men in athletic and heroic scenes, and many of his works have been noted for containing men engaged in what some have read as longing gazes.

Arrow Advertisement Illustration, 1907

In a piece on the artist for the Los Angeles Times, published in 2008 and prompted by the publication of the book J.C. Leyendecker: American Imagist, reporter Carolyn Kellogg offers some insight into how he captured the physique of his beloved "manly men":

Leyendecker’s early style—a crosshatched brush stroke that turned soft surfaces into sharp planes—reinforced Beach’s chiseled good looks. When his dynamic crosshatching faded into softer fills, Leyendecker enhanced the manliness of his subjects in other ways: He lit a single light and oiled the muscles of his models for dramatic contouring. In an early mock-up of an Ivory Soap ad, an erection is prominent in the folds of a bathrobe. Decades before feminist Laura Mulvey wrote about the male gaze objectifying women, Leyendecker turned his gaze toward handsome men and created widely circulated icons of masculinity.

"What you do not find in Leyendecker’s work is the naked female body," collector Alfredo Villanueva-Collado has noted. "It is never shown anywhere. And it’s interesting because one of his influences was Alphonse Mucha, who did many semi-exposed women, but Leyendecker did not. I’ve looked at enough of his work to say this with a degree of certainty."

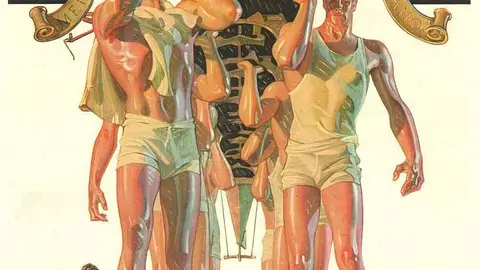

Athlete Before a Mosaic, 1910

With his career booming, Leyendecker and Beach threw lavish parties with famous guests attending. While they might have been restrained in some regards due to the homophobia at the time, they were clearly not living clandestinely.

The good times were not to last, however, with commissions beginning to dwindle over time. By the late 1930s and early 1940s, with tastes changing, he was barely getting any work. When he died in 1951 of a heart attack, at the age of 77, he had little in the way of wealth compared with his heyday. His assets were split between Beach, who died not long after, and his estranged sister—his brother having died in 1924 from a drug overdose.

"Lifeguard, Save Me!"—Saturday Evening Post Cover, August 9, 1924

According to Collectors Weekly, many of his original paintings were sold at a rummage sale for $75 each.

But in recent years, Leyendecker has begun to reemerge as an important artist and cultural figure, with exhibitions of the artist's work popping up around the country, including one currently taking place in Raleigh, North Carolina, at Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

More of his work follows.

The Discus Thrower, 1906

Football Players, 1913

Chesterfield Cigarette Advertisement

Soldiers of the Sea, 1917

America Calls Recruitment Poster

Leyendecker Interwoven Socks Advertisement, circa 1927