Take a Virtual Tour Through This "Art after Stonewall" Exhibition

By Ivan Quintanilla with Daniel Marcus

On June 28, 1969, New York City police raided a gay bar in the West Village named the Stonewall Inn. This time, patrons fought back, marking a watershed moment in the modern fight for LGBTQ equality. The art world—and the world at large—were never the same.

More than 50 years after the famed riots, the Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio has created the first national museum show exploring the impact of the Stonewall Uprising on the visual arts. Art after Stonewall, 1969-1989 looks at two decades of artists working at the intersections of contemporary art, politics, and queer culture. The exhibition, which opened on March 6, features more than 200 works by LGBTQ and straight artists who engaged with queer subcultures during that time.

“We are interested throughout the show in the ways that artists engaged the social movements and social revolution initiated by Stonewall in 1969,” Daniel Marcus, a curatorial fellow at Columbus Museum of Art, tells NewNowNext.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the museum has temporarily closed. Luckily, Marcus has agreed to guide us through some of the exhibition’s highlights, detailing why each piece is an integral part of an art movement that evolved out of Stonewall.

Gran Fury, The Government Has Blood On Its Hands, 1988. Poster, offset lithograph, 31 ¾ x 21 3⁄8 inches (80.65 x 54.29 cm). (Courtesy of Avram Finkelstein)

Named after the Plymouth car model favored by the NYPD, Gran Fury was the self-proclaimed “propaganda ministry” of the AIDS activist group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power). Founded in March 1987, nearly a decade after the first AIDS cases were recorded in the United States, ACT UP quickly emerged as the boldest and most effective activist organization in the struggle to end the AIDS crisis. In keeping with ACT UP’s strategy of collective direct action, Gran Fury created iconic, eye-catching poster designs that communicated the group’s political aims clearly and unambiguously. Bearing a single bloodstained handprint, this poster was first deployed at an ACT UP protest at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) headquarters in Washington, D.C., where activists hoped to “SEIZE CONTROL OF THE FDA,” in order to accelerate clinical testing of potentially life-saving drugs. —Daniel Marcus

Crawford Barton, A Castro Street Scene, 1977. Gelatin silver print, 8 x 10 inches (20.32 x 25.40 cm). Crawford Barton Papers. (Courtesy of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society)

Born and raised in rural Georgia, Crawford Barton felt deeply alienated by the homophobic culture that surrounded him and moved to San Francisco in the late 1960s to live his life as an out gay man. A participant in the first Pride marches, Barton lent his talents to documenting the nascent Gay Liberation movement, becoming one of the foremost photographers of gay life in the Bay Area. Here, Barton depicts a tender moment of public affection between two men in San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood; included in a section of the exhibition called “Coming Out,” this photograph speaks to the jubilant spirit of queer life and love in the first decade after Stonewall. —DM

Sunil Gupta, Untitled #8 from the series Christopher Street, 1976. Archival inkjet print, 11 x 7 ½ inches (27.94 x 19.05 cm). (Copyright and courtesy of the artist and sepiaEYE)

Indian-born photographer Sunil Gupta came to NYC in 1976 to get a Master’s degree in business but fell in love with photography instead. This photograph is part of a series he took of gay men on Christopher Street, the location of the Stonewall Inn and the epicenter of NYC gay life in the 1970s.

“The street was almost exclusively populated by gay men,” Gupta remembers. “For the first time in history, people like me felt able to live proudly, publicly, without shame. It was the first time in my life experiencing that, and it changed me irrevocably. … Really, I was shooting guys I fancied. I wasn’t trying to observe something in a neutral way. I was engaging as a participant. I wanted them to know I’m gay too and that I was drawn to them in some way.” —DM

JEB (Joan E. Biren), Gloria and Charmaine, 1979/2016. Digital silver halide C-type print, 8 ¾ x 12 inches (22.23 x 30.48 cm). Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, Museum purchase 2016.32.1. (Copyright JEB)

One of the foremost photographers of the lesbian movement in the U.S., JEB’s interest in using a camera first emerged out of her involvement in the Furies Collective, a radical feminist-separatist organization founded in Washington, D.C., in 1971. Throughout the ‘70s, JEB travelled across the country chronicling lesbian activism, creative endeavors, and everyday life, amassing a vast archive of images in the process. Between 1979 and 1985, JEB presented her own work alongside other photographs of lesbian life in a two-and-a-half-hour-long slideshow, which came to be known affectionately as “the Dyke Show.” “I wanted my photographs to be seen,” JEB recalls. “I believed they could help build a movement for our liberation." —DM

Diana Davies, Gay Rights Demonstration, Albany, NY, 1971. Digital print, 14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm). (Photo by Diana Davies and copyright The New York Public Library/Art Resource, New York)

Writer, musician, and photojournalist Diana Davies took some of the most iconic photographs of the feminist and LGBTQ movements of the 1970s. Here, Davies focuses her camera on legendary trans activist and performer Marsha “Pay It No Mind” Johnson, one of the key participants in the riot that ignited the Stonewall Uprising. Together with fellow trans activist Sylvia Rivera, Johnson co-founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in the aftermath of Stonewall, advocating for, and providing shelter to, gay and transgender homeless youth and sex workers in lower Manhattan. In this sumptuous photograph, Johnson is seen attending the first statewide march for lesbian and gay rights, held in Albany, New York, on March 14, 1971. —DM

Shelley Seccombe, Sunbathing on the Edge, 1978. Color photograph, 13 x 19 inches (33.02 x 48.26 cm). Private collection. (Copyright and courtesy of the artist)

Manhattan’s West Side Piers became a mecca of gay culture in the 1970s, attracting numerous artists and photographers with their mixture of post-industrial decay and open-air cruising. Photographer Shelley Seccombe became interested in the piers after she and her husband, the sculptor David Seccombe, moved to Westbeth, an artists’ housing complex across from the West Side waterfront. Seccombe claimed that she was drawn to the piers for “their photographic quality; the elegant decaying structures with their peeling paint made an appealing backdrop. […] What kept me coming back and haunting the piers for years was the spontaneous appearance of those unwitting actors, and the majesty of their stage.” —DM

Tabboo!, MARK MORRISROE, 1985. Acrylic on canvas, 68 x 36 inches (172.72 x 91.44 cm). (Photo by Greg Carideo and courtesy of Gordon Robichaux, New York)

Polymath artist, illustrator, musician, drag performer, and stage designer Tabboo! (a.k.a. Stephen Tashjian) loomed large in NYC’s East Village, where he was a regular presence at Club 57, the Mudd Club, CBGB, and the Pyramid Club, among other now-legendary downtown venues. Training in art at Boston’s Massachusetts College of Art and Design, where he met fellow artists Mark Morrisroe (pictured here), Nan Goldin, David Armstrong, and Jack Pierson, Tabboo! moved to NYC in 1982 just as the drag scene was beginning to take off.

“In the beginning, drag was so taboo, especially in the gay world,” Tabboo! remembers. “If you were in drag and walked into a gay bar, they’d throw you out—which the TV show Pose recently reenacted in a great scene. I have this theory, that in the gay world at that time, the most criminal, outsider art that you could possibly do was feminine.” —DM

Gay Liberation Front, Come Out, 1970. Offset lithograph, 14 x 10 inches (35.56 x 25.40 cm). Collection of Flavia Rando. (Copyright 1987 The Peter Hujar Archive LLC., and courtesy of Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco)

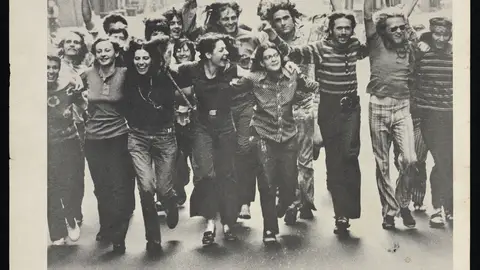

Among the most iconic works in the exhibition is Peter Hujar and Jim Fouratt’s collaboratively designed poster for the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), created in 1970. The photograph for the poster was taken by Hujar, who would later be recognized as one of the most influential photographers of his generation (and an important touchstone for Robert Mapplethorpe, whose work is also featured in Art after Stonewall). Although the photo appears to depict a group of marchers at a protest or Pride parade, the scene was staged by GLF members in lower Manhattan during the early hours of the morning (so as to avoid car traffic). To my mind, the poster ranks among the most significant works of propaganda of the late 20th century: Rather than depict homosexuality as debased or shameful, Hujar makes gay liberation—and gay and lesbian social life in general—look absolutely exhilarating, like an expression of ecstatic joy. By the same token, however, while the image refuses the popular stereotype of queers as effete and lonely, it also leaves the impression that gay liberation was primarily for the young, white, and cisgender. —DM

Keith Haring, Safe Sex, October 20, 1985. Acrylic on canvas tarp. 116 x 116 inches (294.64 x 294.64 cm). (Copyright Keith Haring Foundation)

Among the many artists who joined the ranks of AIDS activists in the late 1980s, Keith Haring bears responsibility for creating some of the movement’s most instantly iconic propaganda. In 1985, he made this massive painting (it measures 10 feet square) as part of a one-man campaign to encourage his fellow gay men—and especially young black and latinx men—to engage in safe(r) sex, selling safe-sex branded t-shirts, posters, and condom cases at Pop Shop, his boutique on the Lower East Side.—DM

Adam Rolston, I Am Out Therefore I Am, 1989. Crack-and-peel sticker, 3 ½ x 3 ½ inches (8.89 x 8.89 cm). (Courtesy of the artist)

Created in June 1989 on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, this crack-and-peel sticker by artist and ACT UP activist Adam Rolston echoes the call to come out that inaugurated the LGBTQ liberation struggle in 1969. Cleverly reworking fellow artist Barbara Kruger’s iconic artwork, I shop therefore I am (1990), Rolston distributed this sticker to demonstrators during the 1989 Pride celebration in NYC, where it became a visual shorthand for the movement for queer civil rights. —DM